Today’s business manager is often reasonably satisfied that profitability is under control, but keeps falling short of his (or her) planned growth targets. If markets are only growing in line with GDP, and further growth in market share is problematic, the only avenue for growth is to launch new businesses into markets where he has not previously competed. The business strategy literature suggests this has a low probability of success. However, every businessman knows that he is the exception to this rule, and will clearly be able to leverage his unique skills and flair to the benefit of all those waiting new customers. His spreadsheet, on conservative assumptions, projects a profitable business within three years and a good return to shareholders thereafter. So why does he fail 75 % of the time? What can be done to increase his chances of success? How can he use evidence-based thinking to replace wishful thinking?

The Profit Impact of Market Strategy (PIMS®) program has collected, over the years, a database of over hundreds of business start-ups in their first five years of life. Data have been provided by managers of the parent company and of the new venture. To count as a start-up, a business has to be new to the parent company on at least two dimensions out of customers, applications, and technologies. The sample is self-selecting. It omits start-ups that failed to survive beyond three years, and freestanding start-ups backed by venture capital not part of a major company. There is, even so, an astonishingly wide spread of results in terms of profitability and growth – enough to draw significant conclusions as to the rules of success versus failure in a corporate environment.

Rule 1: Profitability is not a useful success metric for start-ups

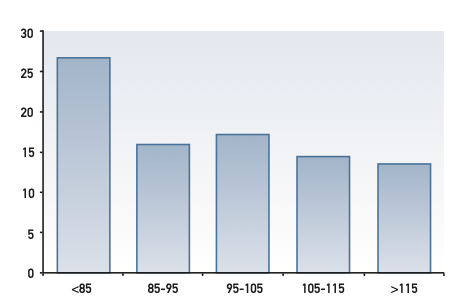

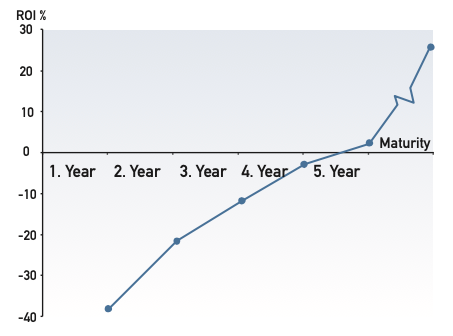

First, the evidence is that start-ups typically lose money, not breaking even until year five. Second, the evidence is that the minority of startups that do make money in years 1 and 2 perform worse at maturity. This is because they can only make money early by skimping on capital investment, product quality, marketing, and second wave innovation. As a result, they miss out on building a strong competitive advantage, which is a key driver of success in maturity.

Rule 2: The key success metric should change as the start-up progresses

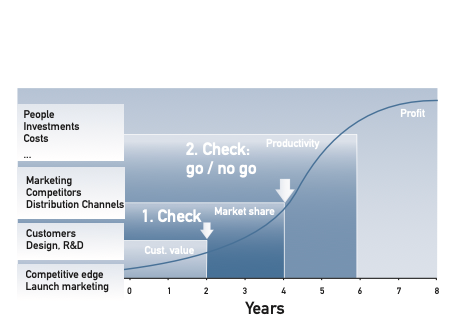

If the start-up is a new entrant to an existing market, then in years 1 and 2 it should focus on building a strong customer perceived value versus the competition. This will depend on product design and positioning, launch marketing, customer service, delivery etc. If this is not established by year 2 it is probably too late: after this a hard-to-change competitive equilibrium takes hold. In years 3 and 4, the success measure should shift to market share. This will depend on having sufficient capacity to meet demand, fighting off competitors’ responses to entry, second wave innovation, and continued improvements in the customer offer. Market share in year 4 is the single most important metric for start-ups: if by year 4 the market penetration is insufficient to yield an economic advantage, it is time to call a halt.

In years 5 and 6 you should be motoring down the experience curve and measuring success by labour and capital productivity, improving the ratio of value added to resources consumed. Then after that it is time to measure success in a conventional way.

Of course, if the start-up is completely unique, it has100 % market share on day one. So here the key success metric in years 1 and 2 has to be creating demand for the product: this similarly will depend on having an attractive value offer, to attract customers money away from broadly-defined alternatives. If this is done, almost certainly competitors will be attracted in, so again the emphasis shifts to market share in year 4. This will depend on having strong intellectual property protection, in addition to the factors listed above for years 3 and 4. Too many “first movers” waste their advantage by being too greedy too early and letting followers in.

Figure 1: Return on investment of start-up businesses in the first 5 years (Source: PIMS start-up Database)

Rule 3: Successful start-ups are aggressive on nearly everything

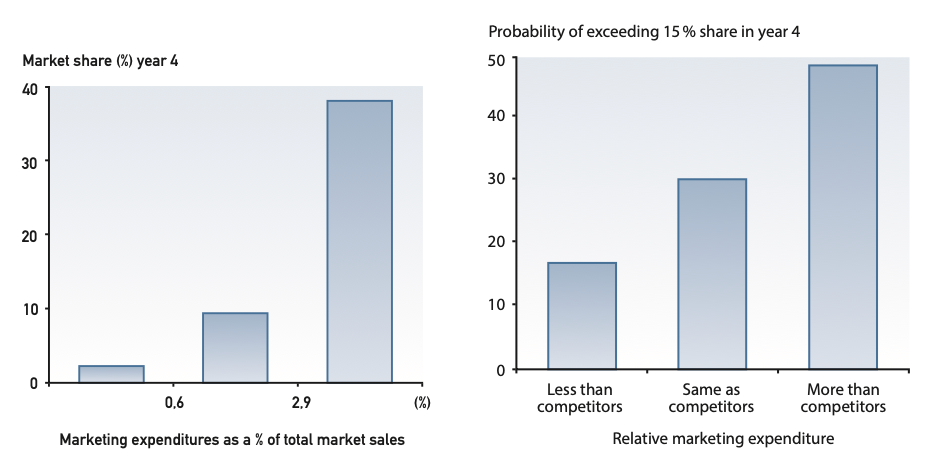

If we look at the single most important success metric – market share in year 4 – we see (Figure 3) that marketing aggressiveness is the most crucial driver. This is true whether we look at marketing spend (advertising, promotion, salesforce, market research, technical support, PR etc.) as a ratio to total served market sales (to capture the absolute aggressiveness) or versus competitors (to capture relative aggressiveness). While there is some circularity in the argument (companies expecting to gain high market share will spend more on marketing), the strength of the relationship is overwhelming. To get customers to buy, you have to create awareness with a big PR and advertising splash, stimulate trial with promotions, create orders by sales force activity, and keep things moving by combining all three.

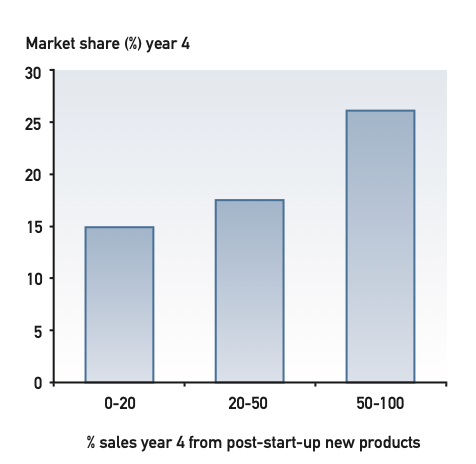

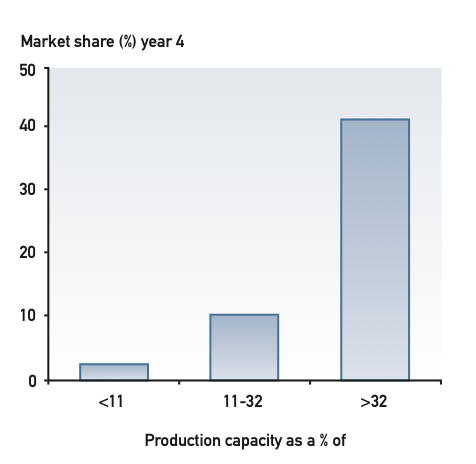

The payoff from aggressiveness does not just apply to marketing: it also applies to innovation and investment in capacity. To count in PIMS as a new product post-start-up, an innovation must be a further step change in either technology or application, and seen as such by customers. Second-wave innovation is important because once you have been in a market for two or three years, competitors have had time to respond to your offering, and negate your original advantage.

Also, you have become more familiar with the customers and their needs, and the products and their technology: you will have many new ideas on how to improve on what you started with.

Usually, capacity takes longer to build, so to succeed you must have enough to meet an optimistic demand scenario: otherwise all you have done is create a nice opportunity for competitors to copy and cash in on your great idea.

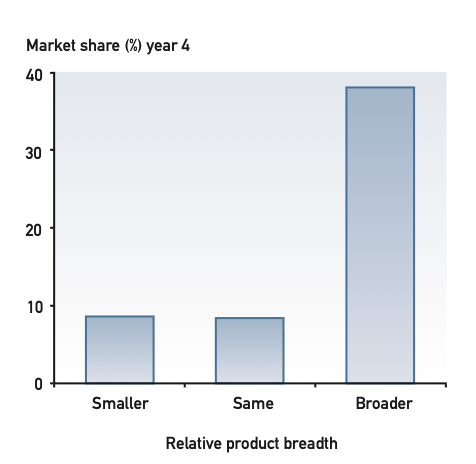

One surprising result for many managers relates to breadth of product offering (Figure 6). Many experts aver that start-ups need to be very focussed: that a rifle is a better weapon than a shotgun. The evidence suggests the opposite, that a shotgun can be a very effective weapon when the rabbit keeps jumping around. Start-up situations are intrinsically uncertain, so it is worth trying a variety of offers to see which ones take off.

Figure 3: Aggressive marketing is critical for market share gain, in both absolute and relative terms

Rule 4: Successful start-ups are clever on price

This is the reason for the “nearly” in rule 3. The problem is that price aggressiveness is the most visible and most copiable weapon in your armoury. Coming in at a small discount to incumbents will very likely cause them to respond in kind, to stop you making inroads on their valuable market franchise. On the other hand, entry at a price premium creates a risk hurdle for customers to try your new offering, even if it is well marketed and appears attractive on the non-price attributes. The best thing is still an aggressively huge discount (based on genuine cost advantages) that competitors cannot bring themselves to match you. This, for example, was the strategy of the discount airlines. But if you can’t do that, price parity is better than a small discount: then, competition can’t be price focussed. The PIMS evidence is in Figure 7.

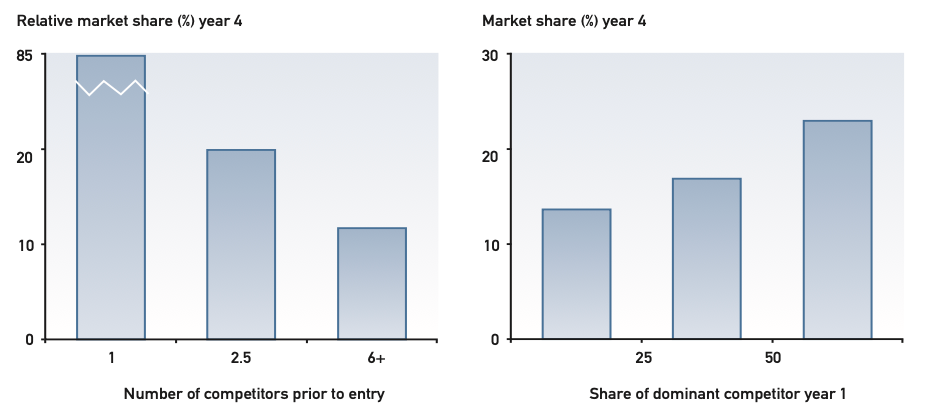

Rule 5: Start-up where the environment favours you

Even if the overall potential arena for your startup is unattractive, in a start-up situation you have the unique discretion to choose which customer/ product group or groups to target. The best option is to find segments with few competitors (preferably with one big fat happy incumbent). The mathematics of dissatisfaction work in favour of the entrant: even if both you and the incumbent have say 10 % dissatisfied customers, more will switch from him to you and fewer from you to him, since he had many more to start with. In a fragmented market, customers have more options to switch to.

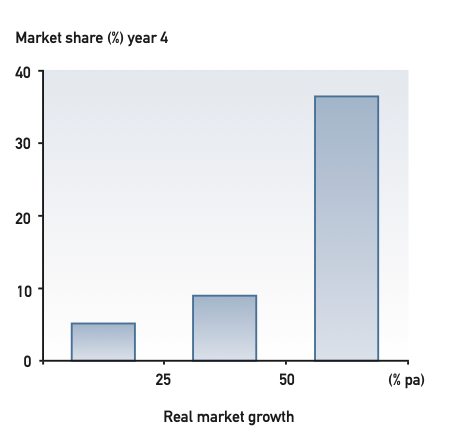

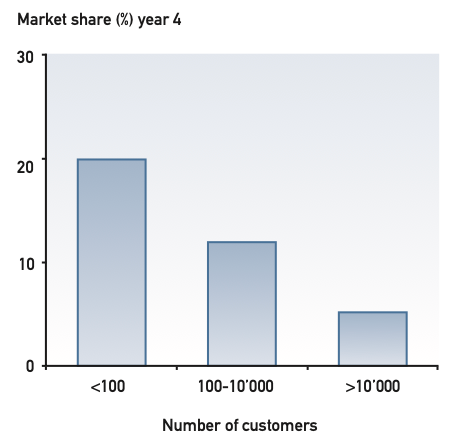

Growing segments are more favourable to new entrants because incumbents can still see growing sales numbers even as their market share declines. This reduces their incentive to compete aggressively. Segments where the customer base is concentrated could be considered a strategic problem due to their bargaining power with suppliers. However, for start-ups it makes market penetration more feasible, since it is easier to grow relationships with relatively few people than a great number.

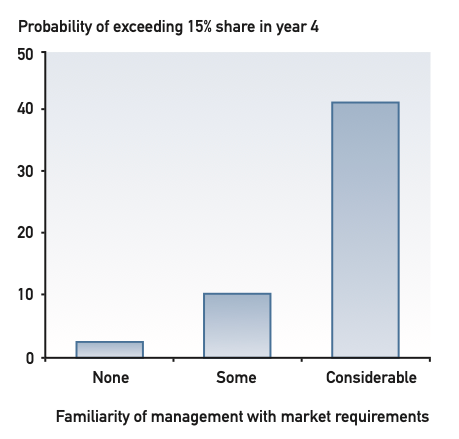

One way of finessing the problem of growing new customer relationships is to enter segments where you have (or can hire) managers already familiar with dealing with the customers, even if for other products. Such management familiarity is strongly correlated with market penetration – much more so than managers’ familiarity with the product technology (see Figure 11).

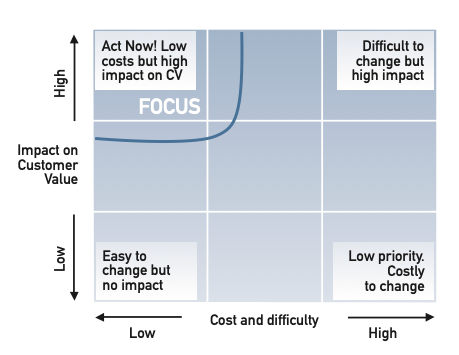

Rule 6: Use customer value as a key driver of your choices

The “raison d’être” for your start-up business is if it provides superior value to customers. It is also the only way to swim in the blue ocean away from the biting sharks. Every strategic choice you make, on which product/market segments to target, on how to engineer your processes, on product design, on which materials to use, even on people and organization, will have an impact on customer value. So any action can be plotted in the matrix in Figure 12: focus on those in the top left corner.

Starting a new venture: PIMS® applications note

Testing your business plans against the experiences of other start-ups in the PIMS® database highlights the impact of competitive realities, and allows you to deal with them before investing your money.

PIMS® users have access to a number of resources that help them to more carefully evaluate the prospects for new businesses. These include (1) a structured process for profiling the new business and its competitors, (2) benchmarks for profitability, market penetration, and discretionary spending, and (3) simulation models to project future profits and cash flow. PIMS® is designed to assist managers in strategic decision-making. The research is carried out by analyzing the experiences of the “confidential insiders case studies” in the data base.

This letter is a brief, non-technical summary of PIMS® evidence on start-ups. It represents only a part of the research results that are used in PIMS® analyses. While it can offer insights on a specific area, it cannot be used to evaluate a business as a whole or to arrive at reliable estimates of the likely effect of a decision. For these purposes, the full range of factors that affect business performance must be taken into account. PIMS® has developed proprietary statistical models that are used to diagnose a start-up business unit’s competitive position and to evaluate alternative strategies.